History of Design

History of Design is concerned with the historical manifestations of collaborative design processes and their products, as well as with the reception, interaction and social relevance of such entities. It is closely connected to the field of teaching Design Theory.

The debate surrounding Modern-Age design is often reduced to the term functionalism. A core theme for the field of teaching is therefore the critical examination of the concept of functionalism, its various forms of reception and its meaning today – the term functional orientation may be more applicable in this context.

Defining epochs

When considering the history of actual Modern-Age design from the mid-19th century to the present day, we find that it was accompanied by astonishingly varied discourse. Whether Postmodernism really did represent a departure and the end of the Modern Age now appears differently to how it did 30 years ago. Heinrich Klotz’s notion of a second Modernism, a term which he coined at the height of the Postmodernist discussion, still seems valid here.

While the first description of a separation of draft and execution in design history can be traced back to Giorgio Vasari’s second edition of Le Vite published in 1560 and to the Accademia delle arti del disegno, which he initiated in 1563 in Florence, the true beginning of a both practice-oriented and theoretical Modernist design came with Gottfried Semper. And with surprising aspects at that. Here, we find purpose and matter addressed, and thereby the relationship between function and material, as well as the “archetypes” in nature, not visible nature, but cell structures, for example. Semper’s call for the compatibility of artefacts with different environments, his focus on the abundance of means and the simultaneous lack of heuristics and not least his thoughts on design education and on the South Kensington Museum in London, co-initiated by him and founded in 1852 as a place for viewing and contemplating design, could bring a different historical dimension to many a discussion today.

John Ruskin, Semper’s antipode, is no less interesting as regards design, politics and economics or – also quite topical – ornament or the intrinsic value of craftwork. Louis Sullivan cannot be grouped with “form follows function” either, as he did not evidence a simple causality of form and function. With Kazimir Malevich and Theo van Doesburg we encounter an approach to design that is at once rationally constructive and spiritual, and with Adolf Loos the statement that “the form of an object lasts, that is to say remains tolerable, ... as long as the object lasts physically”, which precisely does not fundamentally put different areas of design into an ornament-free context and which remains an important distinction regarding artefacts’ linguistic intensity to this day.

Finally, it remains to be noted that there were also distinctly “semantic functionalists”, such as architects Hugo Häring and Hans Scharoun or designers George Nelson, Sori Yanagi, Walter Zeischegg or Max Bill. Ferdinand Kramer also belongs to this group, whose resetting of meanings in apartment furnishing has to be seen against the backdrop of a historicist bombast of meaning and who developed extraordinarily intelligent details and principles in his furniture designs. Knowledge of these and further designers’ work provides a historical basis for a long overdue, but slowly resuming discussion on design and society as well as design and resources. Kenya Hara’s “Designing Design” would be an important contemporary reference, as well as the work of Naoto Fukasawa. Concrete experience concerning the visual half-life of consumer products can in turn be gained by looking at the work of Dieter Rams.

Design history in context

Looking at designed artefacts solely in terms of the history of design does not do the discipline justice. What is needed is a broader perspective on all of design’s spheres of influence, even including its political implications. The directly ‘neighboring disciplines’ are also taken into account in the Offenbach curriculum. Art, architecture and design have seen increasing separation and specialization over the course of industrialization, but efforts to reunite these areas are almost as old as their division – for example in the Arts and Crafts movement, in the Werkbund or at the Bauhaus. Industrial construction before the First World War played an important role here. Many debates were held on the topic, which later also came to include product design. It was not by chance that Peter Behrens was able to work on the architecture, product and communication design of AEG all at the same time before World War One. The Werkbund, Bauhaus, New Frankfurt, the Werkkunstschule movement and HfG Ulm have carried on this aspiration, which today may be seen to have gained a new dimension through digitalization and through the disappearance and re-emergence of real and virtual spaces. Design and architecture are currently converging, and this not just in media façades but primarily in the disposition of real artefacts and digital interfaces in the real and virtual space.

Design and architecture have intrinsic analogies. Both are concerned with use and meaning, exist in a context of activity, have to arrange themselves consensually with third parties in the process of realization and finally are function-bound in all respects. The fine arts are quite different, which despite also being a visual medium, are in every sense radical, experimental, fictional and non-function-bound and as such form a different, yet not unimportant relationship to design.

Design exhibitions at museums are an important medium for the generation of knowledge on design history and its communication. In future corresponding projects are to be developed in cooperation with Frankfurt’s MAK, the Museum of Applied Arts.

In its own projects, the field of teaching is also concerned with fostering a methodical and independent research profile for design history as a discipline.

Current research areas are the design history of the Rhine Main region from the turn of the 20th century to the 1980s, individual phenomena of the New Frankfurt project such as the Frankfurt Kitchen or New Typography, as well as the phenomenon of “morphological transformations” in product design, meaning – as opposed to copying – the intelligent adoption of formal elements in entirely different products.

Alle Objekte sind Sammlungsgegenstände aus der Designsammlung des Museums Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt a.M.

Wire Chair, 1951

Herman Miller Furniture Company (USA), seit 1958 auch Vitra AG (CH)

Ray Berenice Kaiser Eames und Charles Eames (USA) unter Mitarbeit von Harry Bertoia (I/USA)

Ulmer Hocker, 1954

HfG Ulm, heute Zanotta (I), Wohnbedarf (CH) und Vitra (CH)

Max Bil /Paul Hildinger/Hans Gugelot

Radio-Phono-Kombination SK 4, 1956

Max Braun oHG (D)

Dieter Rams (D) und Hans Gugelot (NL)

Panton chair, 1960 (1967)

Vitra (CH)

Verner Panton (DK)

Raacke-Koffer, 1966

Burg Möbel Dieter Ruddies GmbH & Co. KG (D)

Peter Raacke (D)

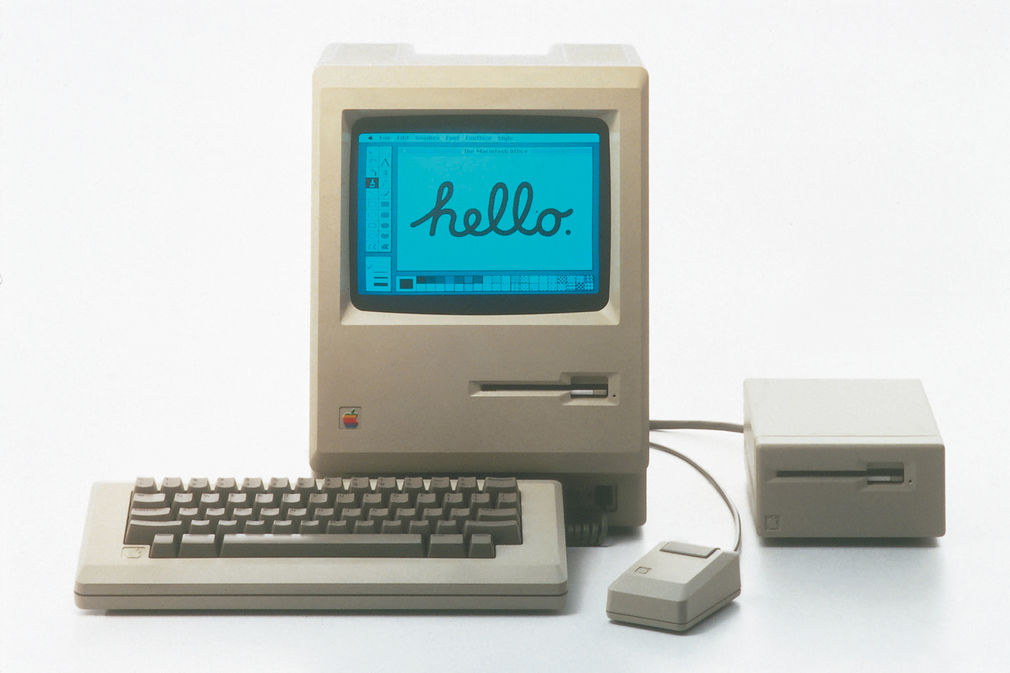

Apple Computer Macintosh, 1984

Apple Inc. (USA)

Hartmut Esslinger (D/USA), frog design

Wasserkessel, 1985

Alessi Spa (I)

Michael Graves (USA)

Raumteiler/Regal Carlton, 1981

Memphis s.r.l. (I)

Ettore Sottsass jr.(I)

Armlehnstuhl Costes, 1985

driade (I)

Philippe-Patrick Starck (F)

Plywood chair, 1988

Vitra AG (CH)

Jasper Morrison (GB)

News

Professorship in Design Theory and History

From winter semester 2014/15 Dr. Klaus Klemp, Deputy Director and curator for design at the Museum Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt will fill the professorship for Theory of Design and HIstory of Design at HfG Offenbach.